17 months of food inflation

18 January 2023

Food and drink prices rose by 16.9% in December, an acceleration on November’s growth of 16.5% and above UK’s inflation of 10.5%. This is the seventeenth month of accelerating annual food and drink inflation, the highest since September 1977. On the month, prices rose by 1.6%.

Topics

- Inflation

- Business insights & economics

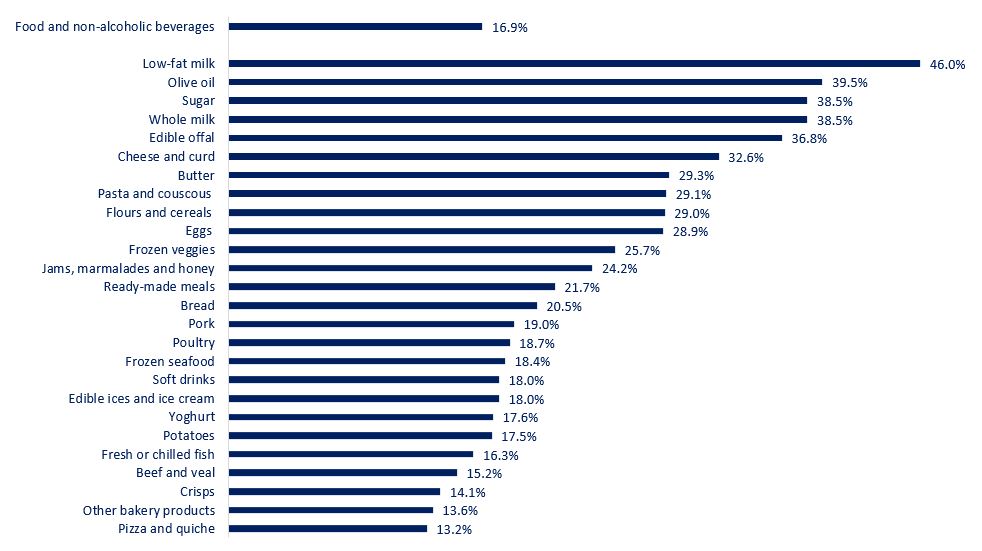

Of the 49 main food categories reported in the official statistics, only six recorded inflation in single-digits. Low-fat milk continues to lead the pack, reaching an eye-watering annual inflation rate of 46.0%, with many categories seeing rises in the 30s: olive oil at 39.5%, sugar at 38.5% and edible offal at 36.8%. Other tubers and tubers vegetables saw the slowest increase in prices at 4.6%.

Food and drink inflation by category

It’s likely that producer prices have continued rising in December. And while that data is not yet available (the ONS will publish it late January), the most recently available showed UK-sourced ingredients were up 18.8% in October and imported ingredients were 31.0% more expensive. Goods leaving manufacturers’ facilities saw inflation reaching 16.1% in October.

The good news is that some pressures are easing, albeit very slowly. Gas prices have been in free fall since the beginning of December 2022. At the time of writing, gas prices on the UK spot market have come down from about a five-fold increase in 2022 to about a 3-fold increase, compared to mid-2021, when they started rising.

Global food prices also fell in December to a level that is slightly lower than a year ago. While a move in the right direction, overall 2022 global food prices were 51% higher than in 2019, with vegetable oils prices more than doubling (126%).

Oil prices are also significantly lower than they were mid-2022, but they are also still higher than pre-pandemic levels. Freight rates and overall global supply stress are moving towards pre-pandemic levels, but there will take some time to get there, with average freight rates still 80% above their pre-COVID level.

If these trends continue, food inflation is likely to peak in mid-2023.

The not so good news is that it will take a while for households to reap these benefits, as manufacturers’ forward contracts with suppliers and fixed-term contracts with customers mean it takes between seven to twelve months for changes in producer costs to feed through onto shop prices.

Unsurprisingly, this impacts the most vulnerable households the most. In November, UK real incomes fell by 2.6%, despite the strongest rise in nominal pay of 6.4% since records began in 2001, the pandemic period notwithstanding. The ONS reported that in December 2022 about half (51%) of adults in Great Britain reported buying less when food shopping in the last two weeks, above the figure of 10% a year ago.

The BRC-KPMG sales figures saw strong headline growth in food and drink sales in December, but volumes were essentially flat, showing that the festive mood had its limits when it came to spending.

In summary, while some cost pressures are easing, our industry is still facing significant challenges for the medium term. The economic slowdown and uncertainty mean that there’s still a long way to go until we’re out of the woods.

Ministers can help our sector by addressing burdensome taxes and unsuitable regulations, to reduce unnecessary costs and bureaucracy facing businesses, particularly SMEs. A clear focus on ensuring our sector is well-placed to grow out of this crisis is critical – swift measures to simplify regulation, reduce red tape, and boost productivity will be decisive.