Another new high for food price inflation

November saw further acceleration in food and non-alcoholic drink inflation, with prices rising by 16.5%, exceeding October’s rate of 16.4%. This is the sixteenth month of accelerating annual food and drink inflation, their highest level since September 1977. On the month, prices rose by 1.1%.

Topics

November saw further acceleration in food and non-alcoholic drink inflation, with prices rising by 16.5%, exceeding October’s rate of 16.4%. This is the sixteenth month of accelerating annual food and drink inflation, their highest level since September 1977. On the month, prices rose by 1.1%.

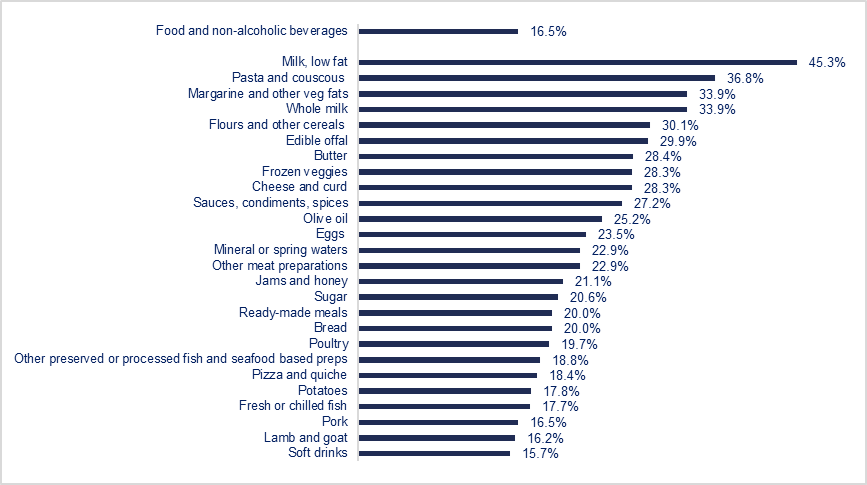

Of the 49 main food categories reported in the official statistics, 41 recorded double-digit inflation. Low-fat milk annual inflation hit 45.3%, while other categories saw high, by historical standards, price rises: Pasta products and couscous (36.8%), whole milk (33.9%), flours and other cereals (30.1%), or frozen vegetables (28.3%). The category ‘other tubers’ saw the slowest increase in prices at 3.2%.

Food and drink inflation by category

Prices of food on supermarkets’ shelves will continue to see persistent rises throughout 2023 and possibly beyond. It takes up to a year for input cost rises to filter through to final prices on shop shelves and manufacturers have now seen costs climbing for over two years. Unfortunately, the ONS has opted not to publish updated producer prices for the month of November, however October showed UK-sourced ingredients were up 18.8% while imported ingredients were 31.0% more expensive. Goods leaving manufacturers’ facilities saw inflation reaching 16.1% in October.

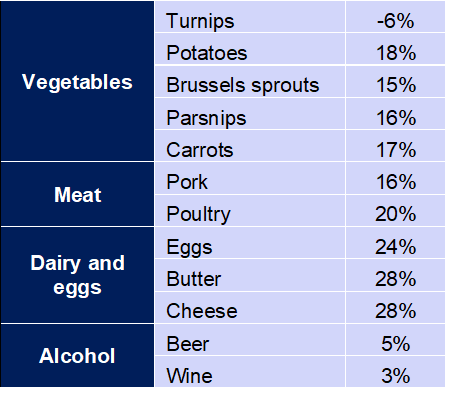

With food and drink inflation rising throughout all of 2022, naturally, households will have to spend more on their Christmas dinner. As shown below, most items traditionally consumed during the festive season have seen double digit price rises in November compared to last year, from poultry and cheese to the humble potato. Turnips are the only product that has seen lower prices in the past year.

The Christmas dinner is more expensive

Note: these are annual changes in prices between November 2021 and November 2022.

All data are ONS statistics of retail prices, except inflation rates of brussels sprouts, carrots, parsnips and turnips, which are wholesale prices sourced from Defra.

Some price pressures are easing for food and drink manufacturers, although too few and at too slow a pace. Global food prices receded slightly in November, falling by 0.1% from October, reaching almost last year’s level. The extension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative and growing Russian exports onto the world market put downward pressures on global prices of wheat, maize and sunflower oil. Nevertheless, overall global prices remain 38% higher than pre-pandemic levels, with vegetable oils 66% and cereals 58% higher.

Despite regaining some of its lost strength, the UK currency remains about 10% weaker against the dollar compared to the beginning of the year. This means that manufacturers, unless they hedge against currency losses or use forward contracts, face increased prices for these commodities, as most are traded in dollars.

Gas prices remain about six times above their long-term trend, with producers reporting a 10-percentage point increase in their energy share of total costs to 22% over the year to Q3 2022. And, the industry is afflicted by serious labour shortages. There were 9.1 vacancies per 100 employees in the food and drink manufacturing in Q3, more than double the UK’s rate of 4.1.

In short, our industry has been facing a cocktail of monumental challenges for almost three years, with virtually each cost component rising persistently, severe staff shortages and extraordinary uncertainty. This has eroded margins and will impact future growth as investment projects are either paused or cancelled. The industry now faces a slowdown in demand, as spending in real terms is slowing down in both retail and hospitality. Retail food sales grew by 5.8% over the three months of November, according to BRC-KPMG data. With food inflation in double digits over that time period, this means that volume sales have fallen.

With high inflation and surging energy prices, this was expected, as households’ real incomes are rapidly eroded. Over the three months to October, average UK real pay fell by 2.7%.

The medium-term outlook is worrying. UK manufacturing output contracted for a fifth consecutive month in November, driven by lower demand and ongoing global supply difficulties.

More troublingly, inflation seems to become more entrenched, raising the question of whether higher interest rates and the resulting economic slowdown will suffice to conquer inflation. The three main indicators of persistent inflation seem to suggest there’s no relief in sight. Inflation is broadening, with more goods becoming more expensive. Annual core inflation (which is the inflation rate stripped of its more volatile components, food and energy) has reached 6.5% in September and October, far exceeding the Bank of England’s 2% target. Nominal wages rose by 6.1% over the three months to October. With low productivity growth, wages are a reasonable indicator of the future path of inflation. Public expectations of UK inflation over the next year have been stuck between 6% and 6.3% since March, both significantly above the 2% monetary policy target.

In short, there are no signs that inflationary headwinds are slowing, meaning that pressures will remain elevated on manufacturers and households alike.

Energy still accounts for a significant portion of companies’ costs, and we are seeking urgent clarity from government on what energy support will be available to the food and drink supply chain in the Spring. The withdrawal of support will undoubtedly put further pressure on food and drink prices. There also remain low cost and high impact measures government could take to reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens on businesses in our sector, which would help curb inflation too