Food inflation slows

Food and non-alcoholic drink annual inflation slowed in April to 19.1% from 19.2% in March, and above CPI’s inflation of 8.7%. This is the second highest food and non-drink inflation since August 1977. On the month, prices rose by 1.4%.

Topics

The decrease in the annual rate was driven by negative contributions from bread and cereals; fish; milk, cheese and eggs; and sugar, jam and honey. Higher vegetables prices pushed the food inflation rate up.

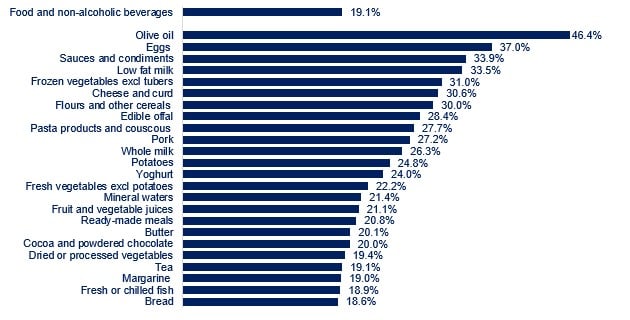

Of the 49 main food categories reported in the official statistics, 44 recorded double-digit inflation, with olive oil seeing the highest rise in prices on the year, at 46.4%, and ‘Other tubers’ the lowest, at 5.2% (see chart).

Food and non-alcoholic drink inflation by category

Source: ONS

Developments in producer prices suggest food and drink inflation is likely to have reached its peak. However, while food and drink inflation will probably slow over the coming months, this only means that prices will continue to rise, just not as rapidly as they have over the past year. Indeed, our modelling suggests food and drink inflation will not reach single-digit territory until 2024. Food and drink manufacturers typically use long-term contracts both with suppliers and customers. This protects consumers from price volatility, but results in cost changes filtering through onto shelf prices with a delay of seven to twelve months.

Food and drink manufacturers saw their costs rise at a slower pace for a second consecutive month. Inflation of UK-sourced ingredients slowed to 9.4% (down from 15.3% in March) and of imported ingredients to 23.4% (down from 28.9% in March). While inflation of goods leaving manufacturers’ facilities – output gate prices, fell to 14.0% (down from 15.5% in March).

In the wider economic environment, some pressures have started easing, but business conditions for manufacturers remain challenging. Global food prices seem to be on a downward trend. In April, they were 20% lower than in March 2022, with all subindices, except sugar, having fallen. Nevertheless, compared to April 2019, prices are 36% higher. Wholesale energy costs have continued to decline since December, although they’re double their pre-pandemic levels, while global shipping disruption has now largely dissipated.

Labour shortages in the sector have eased too, but they remain very high by historical standards. In Q1, the reported vacancy rate in food and drink manufacturing was 5.9%, down from the Q4 rate of 7.0%, but significantly above the 3.1% rate in the overall manufacturing sector or the UK’s overall rate of 3.5%.

The barrage of production cost increases over the last three years means that margins have been eroded. ONS monthly surveys show that a large proportion of food and drink manufacturers have persistently absorbed rising costs. On average, over the year to February 2023, 72% of food and drink manufacturers stated they absorbed a share of their rising costs, compared with, 53% of retailers and 64% of restaurants and cafes, with the difference between manufacturers, retailers and hospitality present each month.

Most food and drink manufacturers, of which 97% are SMEs, operate under relatively low profit margins. With margins squeezed over the last year, producers find themselves in a weaker position to deal with future shocks and, potentially, with lower capital available for investment. This threatens the growth of the industry and the security of the UK food supply chain.

For the medium term, the risks to the industry are a slow economic recovery (which would reduce consumer spend), adverse weather events, like El Niño and Indian El Niño (which would put upward pressures on agricultural commodity prices) and a rise of energy costs in the autumn (currently, futures market bet on higher gas prices in the autumn and winter than current ones).

The picture is sadly not much rosier for households. Food prices rose by 26.2% since August 2021, but pay growth has significantly lagged, with private sector wages rising only 10.6%.

Poorer households are bearing the brunt of food price inflation. A lower income naturally means a larger proportion of one’s budget is spent on food. The 10% of the UK population on the lowest income spent approximately 18% of their disposable income on food and non-alcoholic drink in the financial year ending 2021, above 12%, the corresponding share of the wealthiest 10% of the population, and above 14%, the average share. With real incomes eroding since ONS released these statistics, it is likely that households are now spending an even higher proportion of their budget.

Worryingly, many people are dealing with the rise in prices by buying less food, with about half of the population reporting lower food purchases over the last year, compared to fewer than 10% in October 2021 (see chart).

Percentage of adults stating they are buying less food

Source: ONS, Opinions and lifestyle surveys

In the wider economy, while inflation eased, core inflation (a measure of inflation excluding more volatile items, such as food and energy), accelerated to 6.8% from 6.2% last month, its highest since March 1992, and significantly above the Bank of England’s 2% target. With pay growth also outpacing the 2% target – 7.0% for the private sector and 5.6% for the public sector in March, a fresh increase in interest rates in June is not out of question.

Government can help our industry by urgently reviewing upcoming packaging recycling regulations to make them more efficient, by working with us to address labour and skills shortages, and by scrapping costly plans to extend ‘not for EU’ labelling requirements needed for businesses to access green lanes into Northern Ireland on a UK-wide basis.