Industry’s employment falls in Q1

Employment in the food and drink manufacturing fell in Q1. The industry offered 3,000 fewer jobs in Q1 compared to Q4, and 8,000 fewer jobs compared to Q1 2022. This brings the total number of jobs in the industry to 451,000.

Topics

Jobs in the food and drink manufacturing – total and 4-quarter averages (in ‘000)

Source: ONS, JOBS03 and JOBS04 series

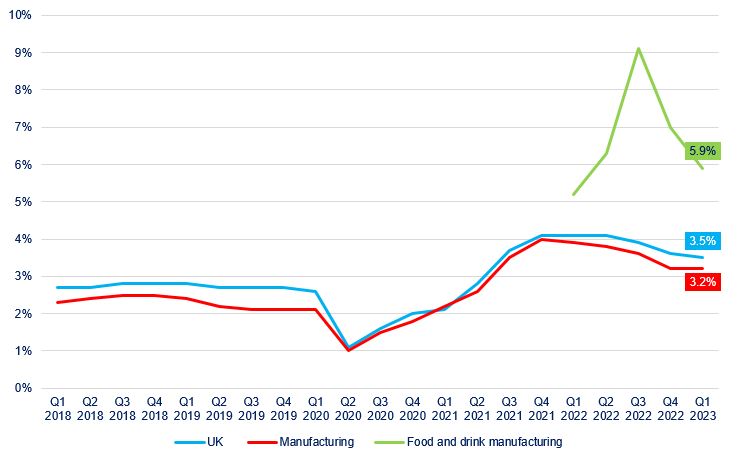

At the same time, industry’s labour vacancies fell to 5.9% in Q1 compared to 7.0% in Q4, the lowest rate since Q1 2022 (5.2%). However, they remain uncomfortably high at almost double the rate of UK manufacturing as a whole of 3.2% and above the UK’s rate of 3.5%. Moreover, vacancies remained widespread across roles and skills, with manufacturers struggling to fill high-skilled positions (R&D specialists, engineers, sales & marketing, IT, finance, HR, and legal), technical roles (bakers or food technologists) and lower-skilled positions (production and machine operatives, drivers, packing operators, maintenance technicians). Labour shortages continue to hold back growth – with some manufacturers unable to take on new orders due to the lack of available staff and skills.

Vacancy rates in the food and drink manufacturing, UK and manufacturing

(number of vacancies/ 100 employees)

Source: ONS and FDF State of Industry Surveys

The industry has experienced substantial pressures over the last couple of years which have eroded its resilience. Food and drink manufacturing insolvencies are on the rise. In 2022, the industry saw its insolvency rate doubling compared to the rate of 2019, contrasting starkly with to a rise of 25% in Great Britain. It seems like there’s more to come this year, with 71 insolvencies already recorded in Q1 2023. This amounts to 58% of all 2019 insolvencies in the sector, compared to 38% for GB as a whole.

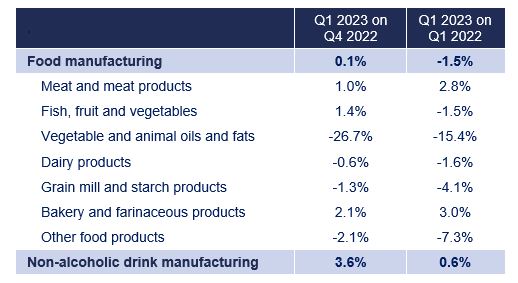

Growth in some subsectors has slowed already. In Q1, compared to a year ago, food manufacturing output was 1.5% smaller than a year ago, with other subsectors also shrinking. As the cost of living crisis hit British households hard, this is not surprising. Worryingly, many people are dealing with the rise in prices by buying less food, with about half of the population reporting lower food purchases over the last year, compared to fewer than 10% in October 2021.

Growth by sector, Q1 2023

Source: ONS

In the short-term, the combination of lower demand and an inability to pass on cost increases are the biggest risks to industry’s growth. For the medium-term, a slower UK economic recovery, climate change and poorly designed government regulations will further inhibit investment and growth.

But as the UK labour market is holding up well, it looks like the Bank of England will continue rising interest rates, slowing both the UK economy growth and the prospects of consumer spend recovery.

The UK saw its number of employed people reaching a record high in May. Employment rose 0.2 percentage points on the quarter to 76.0%, although it remains below pre-pandemic level, while the inactivity rate fell 0.4 percentage points. However, vacancies continued to fall, reaching the lowest level since September 2021, as hiring has eased.

And while this might signal a beginning of a cooldown in the labour market, this is happening at a slower pace than desired by policy makers, as evidenced by the strong strides in pay growth in April. Wages in the private sector increased by 7.6% on the year, above market expectations and the highest growth recorded outside of the pandemic period, while public wages rose by 5.6%, the highest rate since October 2003. At the same time, core inflation accelerated to 6.8% in April, its highest level since March 1992.

This means that the Bank of England will very likely attempt to rein in inflation by further increasing interest rates – markets now expect rates to climb to 5.5% by the end of the year. But the relatively high and accelerating levels of both pay rises and core inflation suggest that it’ll take a long time for inflation to reach the 2% target. While higher interest rates will increase borrowing costs for investment, government and mortgage lenders.

Many food and drink manufacturers are looking to invest more in advanced technologies as a result of skills shortages, but the uncertain economic outlook and the range of upcoming, complex government regulation is holding them back. Automation can ease some of the pressures, but we need to make it easier for more businesses to access support and invest.

We welcome the UK Government’s independent review into labour shortages across the food chain and look forward to its imminent publication. But given the urgency of the problem, it should focus on measures which could make a difference right now. We need solutions that create a more flexible labour market, make the skills system work better for our businesses, as well as a reformed and more flexible Apprenticeship Levy.